The Blitz

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Blitz was the sustained bombing of Britain by Nazi Germany between 7 September 1940 and 10 May 1941,[1] during the Second World War. The Blitz hit many towns and cities across the country, but it began with the bombing of London for 76 consecutive nights.[5] By the end of May 1941, over 43,000 civilians, half of them in London, had been killed by bombing and more than a million houses were destroyed or damaged in London alone.[6][7]

London was not the only city to suffer Luftwaffe bombing during the Blitz. Other important military and industrial centres, such as Aberdeen, Barrow-in-Furness, Belfast, Bootle, Birkenhead, Wallasey, Birmingham, Bristol, Cardiff, Clydebank, Coventry, Exeter, Glasgow, Greenock, Sheffield, Swansea, Liverpool ,[8] Hull, Manchester, Portsmouth, Plymouth, Nottingham, Brighton, Eastbourne, Sunderland, and Southampton, suffered heavy air raids and high numbers of casualties. Hull was the most heavily bombed city after London with 85% of its buildings being destroyed or affected. Birmingham and Coventry were very badly affected because of the Spitfire and Tank plant being based in Birmingham and the many other munitions factories in Coventry. Coventry was almost totally destroyed.

Smaller bombing raids were made on Edinburgh, Newcastle, York, Exeter, and Bath. Oxford was not bombed because Adolf Hitler wanted it to be his capital;[9] Blackpool also escaped heavy bomb damage as Hitler wanted to use it for entertainment.[10][11] Hitler's aim was to destroy British civilian and government morale.

Its intended goal of demoralizing the British into surrender unachieved,[12] the Blitz did little to facilitate potential German invasion. By May 1941, the imminent threat of an invasion of Britain had passed and Hitler's attention was focused on Operation Barbarossa in the East. Although the Germans never again managed to bomb Britain on such a large scale, they carried out smaller attacks throughout the war, taking the civilian death toll to 51,509 from bombing. In 1944, the development of pilotless V-1 flying bombs and V-2 rockets briefly enabled Germany to again attack London with weapons launched from the European continent. In total, the V weapons killed 8,938 civilians in London and the south-east.[13]

Contents |

Prelude

After the Battle of France, the Battle of Britain began in July 1940. From July to September, the Luftwaffe frontally attacked Royal Air Force Fighter Command to gain air superiority as a prelude to invasion. This involved the bombing of fighter airfields to destroy Fighter Command's ability to combat an invasion. Simultaneous attacks on the aircraft industry were carried out to prevent the British replacing their losses, but these were ineffective; changes introduced by Lord Beaverbrook ramped up the efficiency of fighter production markedly. Machine replacements were arriving at a rate three times higher than German intelligence believed. The pressure on pilot replacements was much more intense, and eventually overcame official reluctance to put experienced pilots from Poland, Czechoslovakia, and other occupied nations in front line combat.

In late August 1940, before the date normally associated with the start of the Blitz, the Luftwaffe attacked industrial targets in Birmingham and Liverpool. This was part of an increase in night bombing brought about by the high casualty rates inflicted on German bombers in daylight. The first German plane to be shot down was over Edinburgh after a failed attempt to bomb the Forth Rail Bridge. Also, the docks of Edinburgh and surrounding suburbs were attacked, including a whisky factory which caused a fire for several days.

Two months earlier - on 21 June 1940 - R. V. Jones briefed Churchill on Knickebein - a radio beam guidance system used by by the Luftwaffe for bombing through cloud cover. In the resulting Battle of the Beams the British were able to 'bend the beams', influencing the drop point of German raids so that the targets were missed completely.

During a raid on Thames Haven, on 24 August, some German aircraft (one commanded by Rudolf Hallensleben who went on to win the Knights Cross for other actions)[14] strayed over London and dropped bombs in the east and northeast parts of the city, Bethnal Green, Hackney, Islington, Tottenham, and Finchley. It is not known with certainty whether this was a navigational 'bungle' or a direct result of anti-Knickebein measures.

In any event, the incident prompted the British to mount a retaliatory raid on Berlin the next night with bombs falling in Kreuzberg and Wedding, causing 10 deaths. Hitler was said to be furious, and on 5 September, at the urging of the Luftwaffe high command, he issued a directive "for disruptive attacks on the population and air defences of major British cities, including London, by day and night". The Luftwaffe began day and night attacks on British cities, concentrating on London. This relieved the pressure on the RAF's airfields.

Prior to the beginning of the Blitz, dire predictions were made about the number of people who would be killed by a German bombing campaign. A report by the Ministry of Health commissioned in spring 1939, calculated that during the first six months of aerial bombardment there would be 600,000 people killed and 1.2 million injured.[15] This proved to be greatly over-estimated because it was based upon faulty assumptions about the number of German bombers available and the average number of casualties caused by each bomb. However, it led to the mass evacuation of around 650,000 children to the countryside.

Commencement of the Blitz on September 6

There is a misconception that the Blitz started on September 7, 1940. Bombs began dropping the night of September 6 and continued for the full day of the 7th and on into the morning of the 8th. Saturday 7th was the first full day and has officially and erroneously become the day the Blitz started. Hermann Göring launched bombers and the first bombs caused damage the night of September 6, the day the Blitz started.

The first damage to property on September 7 was recorded at eight minutes past midnight, a grocer’s shop at 43 Southwark Park Road, SE16. [16]

Quoted in the The Manchester Guardian is Göring's communiqué: Attacks of our Air Force on objectives of special military and economical value in London, which began during the night of September 6, were continued during the day and night of September 7 with exceptionally strong forces using bombs of the heaviest caliber. [17]

First phase

The first intentional air raids on London were mainly aimed at the Port of London, causing severe damage. Late in the afternoon of 7 September, 364 bombers attacked, escorted by 515 fighters. Another 133 bombers attacked that night. Many of the bombs aimed at the docks fell on neighbouring residential areas, killing 436 Londoners and injuring 1,666.

Few anti-aircraft guns had fire-control systems, and the underpowered searchlights were usually ineffective against aircraft at altitudes above 12,000 feet (3,600 m). Even the fortified Cabinet War Rooms, the secret underground bunker hidden under the Treasury to house the government during the war, were vulnerable to a direct hit. Few fighter aircraft were able to operate at night, and ground-based radar was limited.

During the first raid, only 92 guns were available to defend London. The city's defences were rapidly reorganised by General Sir Frederick Pile, the Commander-in-Chief of Anti-Aircraft Command, and by 11 September twice as many guns were available, with orders to fire at will. This produced a much more visually impressive barrage that boosted civilian morale and, although it had little physical effect on the raiders, encouraged bomber crews to drop before they were over their target.

During this first phase of the Blitz, raids took place day and night. Between 100 and 200 bombers attacked London every night but one between mid-September and mid-November. Most bombers were German, with some Italian aircraft flying from Belgium. Birmingham and Bristol were attacked on 15 October, and the heaviest attack of the war so far – by 400 bombers and lasting six hours – hit London. The RAF opposed them with 41 fighters but shot down only one Heinkel bomber. By mid-November, the Germans had dropped more than 13,000 tons of high explosive and more than 1 million incendiary bombs for a combat loss of less than 1% (although some aircraft were lost in accidents inherent to night flying and night landing).

Second phase

From November 1940 to February 1941, the Luftwaffe attacked industrial and port cities. Targets included Coventry, Southampton, Birmingham, Liverpool, Clydebank, Bristol, Swindon, Plymouth, Cardiff, Manchester, Sheffield, Swansea, Portsmouth, and Avonmouth. During this period, 14 attacks were mounted on ports excluding London, nine on industrial targets inland, and eight on London.

Probably the most devastating raid occurred on the evening of 29 December, when German aircraft attacked the City of London itself with incendiaries and high-explosive bombs, causing a firestorm that has been called the Second Great Fire of London. A photograph showing St Paul's Cathedral shrouded in smoke (shown in the information box at the top of this article) became a famous image of the times.

Final attacks

In February 1941, Karl Dönitz persuaded Hitler to attack British seaports in support of the Kriegsmarine's Battle of the Atlantic. Hitler issued a directive on 6 February ordering the Luftwaffe to concentrate its efforts on ports, notably Plymouth, Barrow-in-Furness, Clydebank, Portsmouth, Bristol, Avonmouth, Swansea, Liverpool, Belfast, Hull, Sunderland, and Newcastle. Between 19 February and 12 May, Germany mounted 51 attacks against those targets, with only seven directed against London, Birmingham, Coventry, and Nottingham.

By now the imminent threat of invasion had all but passed as Germany had failed to gain the prerequisite air superiority. The aerial bombing was now principally aimed at the destruction of industrial targets, but also continued with the objective of breaking the morale of the civilian population,[18] and in this respect the raids were widely perceived by the British as an attempt to terrorise the population.[19] British defences were much improved by this time with ground-based radar guiding night fighters to their targets and the Bristol Beaufighter, with airborne radar, proved to be effective against night bombers.

An increasing number of anti-aircraft guns and searchlights were radar-controlled, improving accuracy. From the start of 1941 the Luftwaffe's monthly losses increased (28 in January, 124 in May). Belfast however remained poorly defended, with just seven anti-aircraft guns. When the city was attacked on the night of Easter Tuesday 1941, it suffered the greatest loss of life in a single raid on the United Kingdom outside London, her guns having stayed silent for fear of hitting defending RAF fighters, which had not been scrambled. The impending invasion of the Soviet Union required the movement of German air power to the east, and the Blitz ended in May 1941.

The last major attack on London was on 10 May: 515 bombers destroyed or damaged many important buildings, including the British Museum, the Houses of Parliament, and St. James's Palace. The raid caused more casualties than any other: 1,364 killed and 1,616 seriously injured.[15] Six days later 111 bombers attacked Birmingham; this was the last major air raid on a British city for about a year and a half.[15]

Civilian and political reactions

The civilians of London had an enormous role to play in the protection of their city. Many civilians who were not willing or able to join the military became members of the Home Guard, the Air Raid Precautions Service, the Auxiliary Fire Service, and many other organizations. During the Blitz, Boy Scouts guided fire engines to where they were most needed, and became known as the Blitz Scouts.[20]

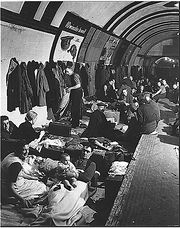

During the Blitz, far fewer dedicated public bomb shelters than necessary were available. The government feared that a "shelter mentality" would develop if people were provided with central deep shelters. This was one of the reasons behind the preference for getting people to construct Anderson shelters in their back gardens. The authorities in London, after being put under very considerable pressure from public opinion, did make use of about 80 underground Tube stations to house about 177,000 people. In contrast, the Germans made a much more concerted and organized effort to shelter their population against the Allied strategic bombing campaign later in the war.

Another frequent response to bombing was what became known as "trekking". Many thousands of civilians slept far from their homes and travelled several hours into work and several hours out again every day. Official sources often denied this was happening.

British civil defence preparations for the Blitz were also influenced by the work of Ramon Perera, a Catalan engineer. Perera supervised the building of some 1,400 public shelters in Barcelona during the Spanish Civil War. They proved a great success, with no one being killed in the shelters despite frequent heavy air raids on the city. The measures impressed the British structural engineer Cyril Helsby who went to Barcelona in December 1938 on a fact-finding visit sponsored by the Labour Party. When Barcelona fell to the Spanish Nationalists in January 1939, Helsby persuaded British secret services to help Perera reach Britain; he arrived shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War.

However, the British authorities were slow to act on Perera and Helsby's advice that simple but effective public shelters should be built, opting instead for makeshift Anderson shelters for family protection. It is possible that this decision proved costly in injuries and fatalities, as one contemporary confidential report putatively suggests. Historian Paul Preston has controversially alleged that the British government took a utilitarian view and regarded its duty to protect civilians from aerial blitzkrieg as secondary to strategic considerations in a time of war, resulting in much loss of life but saving many more in the long run.[21]

Yet the bombing of London in this period was far more intensive, persistent and devastating than the bombing in Spain. Just before the war, British Ministry of Health studies into the effects of aerial bombardment predicted 600,000 dead in a full scale aerial assault.[15] The mortality rate of the actual assault, severe as it was, emerged as less than 10% of this estimate, which represented a triumph of planning in the face of such terror, though the actual physical, emotional and economic damage remained incalculable.

Great improvements were made to air defences during the Blitz. The air defences and the stoicism of the British people were used for propaganda. American radio journalist Edward R. Murrow was stationed in London at the time of the Blitz, and he made live radio broadcasts to the United States during the bombings. Live broadcasts from a theatre of war had not been heard by radio audiences before, and Murrow's London broadcasts made him a celebrity. His broadcasts were enormously important in reinforcing and focusing the growing sympathy the majority of the American people already felt for Britain's suffering and bravery.

Other attacks

Baedeker Blitz

The Baedeker Blitz was a series of raids conducted in mid-1942 as reprisals for the RAF bombing of the German city of Lübeck. The Baedeker raids, named for the famous tourist guidebooks,[22] targeted historic cities with no military or strategic importance such as Bath (bombed April 25–26), Canterbury (bombed June 1), Exeter, Norwich, and York between February to May 1942. Churches and other public buildings of interest were often the targets of these 'retaliatory raids' (Vergeltungsangriffe) in an attempt to break civilian morale. These and other strategically insignificant historic cities in Britain suffered severe damage, and major landmarks such as the Guildhall in York and the Assembly Rooms in Bath were seriously damaged.[23] There was also considerable loss of life (over 1600 fatalities).

Baby Blitz

In November 1943, Reichsmarschal Hermann Göring ordered the Luftwaffe to resume mass bomber attacks against southern England. During December 1943 and early January 1944, the Luftwaffe gathered some 515 aircraft of widely differing types on French airfields. On 21 January 1944, the Luftwaffe made the first mass attack on London since 1941. 447 bombers were sent out, including Junkers Ju 88s, Ju 188s, Dornier Do 217s, Messerschmitt Me 410 Hornissen, and examples of the then-new Heinkel He 177 Greif, the Luftwaffe's only operational heavy bomber. The bomber crews generally lacked night-flying experience, and the aircraft types had very different performance, which required the use of pathfinder aircraft to mark targets. Only 32 of the 282 bombs dropped fell on London that night.

The raids continued for the next three months, to little effect, for the loss of 329 aircraft. Furthermore, these aircraft were not available to defend against the forthcoming Allied invasion of continental Europe. By 1 July 1944 Sperrle had only 90 bombers and 70 fighters available in western Europe (Luftflotte 3).[24]

V-Weapons offensive

On 12 June 1944, the first V-1 flying bomb attack was carried out on London. A total of 9,251 V-1s were fired at Britain, with the vast majority aimed at London; the 2,515 that reached the city killed 6,184 civilians and injured 17,981. In one instance, on 3 July 1944, 74 American military personnel died in what was later categorized as the single worst loss of life for American servicemen in London when a V-1 bomb fell over Sloane Court East / Turks Row in southern London.[25] Over 4,000 V-1 bombs were destroyed by the Royal Air Force, the Army’s Anti-Aircraft Command, the Royal Navy, and barrage balloons.[13]

The V-2 Rocket was first used against London on 8 September 1944. An estimated 2,754 people in London were killed and 6,523 injured by the 1,115 V-2s that were fired at the United Kingdom. A further 2,917 service personnel were killed as a result of the V weapon campaign.[13]

On 17 September 1944, the blackout was replaced by a partial "dim-out".

At the end of the Blitz, an estimated 16,000 had been killed and 180,000 injured.

Major sites and structures damaged or destroyed

- All Hallows by-the-Tower

- All Hallows-on-the-Wall

- All Saints Notting Hill

- Arsenal Stadium

- Bakers Row EC1

- Balham tube station – 14 October 1940

- Bank tube station – 11 January 1941

- Big Ben – 10 May 1941

- Birmingham Cathedral – 7 November 1940

- Bounds Green station – 13 October 1940

- British Museum – 10 May 1941

- Broadcasting House - 15 October 1940

- Buckingham Palace

- Bull Ring Market Hall, Birmingham

- Café de Paris – 8 March 1941

- Central Telegraph Office – 29 December 1940

- Charles Church, Plymouth – 20–21 May 1941

- Chelsea Old Church

- Christ Church, Newgate

- Coventry Cathedral

- Coventry and Warwickshire Hospital

- Cross Street Chapel, Manchester, December 1940

- Dutch Church

- Domus Dei, Portsmouth – 10 January 1941

- Euston station – 15 November 1940

- Free Trade Hall

- Great Synagogue of London – 10 May 1941

- Guildhall – 29 December 1940

- Holland House

- Houses of Parliament – 10 May 1941

- Lambeth Palace – 10 May 1941

- Lambeth Walk – 18 September 1940

- Leeds Town Hall – 15 March 1941

- London Library

- Manchester Cathedral – December 24, 1940

- Manchester Piccadilly

- Manchester Victoria station

- Marble Arch Underground station – 17 September 1940

- National Portrait Gallery – 15 November 1940

- Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham – May, 1941

- Old Bailey – 10 May 1941

- Old Trafford – 11 March 1941

- Palace Theatre – September 1940

- Paternoster Row – 29 December 1940

- Portsmouth Guildhall

- Portsmouth Harbour railway station

- Queen's Hall – 10 May 1941

- Royal Exchange, Manchester

- Shell Mex House – 15 September 1940

- Saint Mary's Guildhall, Coventry

- St. Joseph's RC Primary school – 10 May 1941

- St Alban Wood Street

- St Alfege's Church, Greenwich – 19 March 1941

- St. Andrew-by-the-Wardrobe

- St Andrew Holborn

- St Ann's Church – December 1940.

- St Augustine Watling Street

- St Bartholomew the Less

- St Botolph Aldersgate

- The Cathedral Basilica of St Chad, Birmingham – November 1940

- St. Clement Danes

- St Dunstan-in-the-East

- St George in the East – May 1941

- St James Garlickhithe

- St. James's Palace – 10 May 1941

- St Lawrence Jewry – 29 December 1940

- St Luke's Church, Liverpool

- St Mary Abchurch

- St Mary Aldermanbury

- St Mary-le-Bow – 10 May 1941

- St Mary's Church, Swansea – February 1941

- St Nicholas Cole Abbey

- St Olave Hart Street

- St Paul's Cathedral – 29 December 1940

- St Peter's Hospital, Bristol

- St Thomas Church, Birmingham

- St Vedast alias Foster

- Temple Church

- Trafford Park, Manchester. 23 December 1940

- Villa Park, Birmingham

- Watts Warehouse, Manchester

- Westminster Abbey – 15 November 1940

- Westminster Hall – 10 May 1941

See also

- ARP

- Barrow Blitz -Luftwaffe bombing in Barrow-in-Furness

- Butterfly Bomb

- Churchill Museum and Cabinet War Rooms

- Cyril Demarne- London fireman

- Military history of the United Kingdom during World War II

- Operation Sea Lion

- The Emergency- Luftwaffe bombing in Ireland

- The Second Great Fire of London

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Stansky 2007, p. 3

- ↑ Hooton 1997, p. 42.

- ↑ Haigh, Christopher (1990). The Cambridge historical encyclopedia of Great Britain and Ireland. Cambridge University Press. p. 317. ISBN 978-0521395526.

- ↑ Murray 1983, p. 55.

- ↑ Some authorities say 57 consecutive nights, and some say 76, depending on how one accounts for 2 November, which was too cloudy for bombing.

- Docklands at War: the Blitz Museum of London

- Stansky, Peter. September 7, 1940: The first day of the London Blitz. That story and does 9/11 change how we view it? Stanford University

- ↑ "Air Raid Precautions – Deaths and injuries". Myweb.tiscali.co.uk. http://myweb.tiscali.co.uk/homefront/arp/arp4a.html. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ↑ Remembering the Blitz Museum of London

- ↑ http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/maritime/exhibitions/blitz/blitz.asp

- ↑ http://www.oxfordmail.co.uk/news/1717202.hitlers_oxford_plans_revealed/

- ↑ http://www.blackpoolgazette.co.uk/ve-day-supplement/Stan39s-war-memories.1016538.jp

- ↑ http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2009/feb/23/hitler-blackpool-resort-plans

- ↑ Murray, p 45

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 The V Weapons Campaign Against Britain, 1944–1945 Imperial War Museum

- ↑ Stallwood, Oliver. Bungling pilot 'triggered blitz' , Metro, 10 October 2006 page 24. citing papers to be auctioned at Ludlow Racecourse on 25 October 2006

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Price, Alfred. Blitz on Britain 1939–45, Sutton Publishing (2000), ISBN 0-7509-2356-3

- ↑ "London Blitz 1940: the first day's bomb attacks listed in full". 2010. http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/datablog/2010/sep/06/london-blitz-bomb-map-september-7-1940?showallcomments=true. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- ↑ "Goering directing the attacks on London". Fox News. 2008.

- ↑ Murray

- ↑ "Bombing raids of World War Two". Century-of-flight.net. 1940-09-07. http://www.century-of-flight.net/Aviation%20history/WW2/blitz.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ↑ "An Official History of Scouting". http://www.scouts.org.uk/book. Retrieved 2007-05-01.

- ↑ Montse Armengou, Ricard Belis. (2007). Ramon Perera, The Man Who Saved Barcelona. [television]. Catalonia: TV3.

- ↑ A.C. Grayling (2006); Among the dead cities; Bloomsbury (2006); ISBN 0-7475-7671-8 . Pages 50–52

- ↑ Fact File : Baedeker Raids) BBC: People's War

- ↑ Mitcham, p.12

- ↑ See the unit history of the 130th Chemical Processing Company, page 11.

References

- Hooton, E. (1997). Eagle in Flames: The Fall of the Luftwaffe. Arms & Armour Press. ISBN 9781854093436.

- Levine, Joshua (5 October 2006). Forgotten Voices of the Blitz and the Battle for Britain. Ebury Press. ISBN 9780091910037.

- Mitcham, Samuel W (2007). Retreat to the Reich: The German Defeat in France, 1944. Stackpole. ISBN 9780811733847.

- Murray, Williamson (1983). Strategy for defeat : the Luftwaffe 1933–1945. Diane. ISBN 9781428993600.

- Price, Alfred (2000). Blitz on Britain 1939–45, Sutton Publishing, ISBN 0-7509-2356-3

- Ramsay, Winston The Blitz — Then & Now, Volumes 1–3, After The Battle Publications, 1987–89

- Stansky, Peter (2007). The First Day of the Blitz. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300125566.

- Titmuss, R. M.(1950) Problems of Social Policy (part of the Official History) Appendix 7: Weight of Bombs dropped on UK 1939–45

External links

- The Blitz Original reports and pictures from The Times

- The Blitz: Sorting the Myth from the Reality, BBC History

- Exploring 20th century London – The Blitz Objects and photographs from the collections of the Museum of London, London Transport Museum, Jewish Museum and Museum of Croydon.

- Liverpool Blitz Experience 24 hours in a city under fire in the Blitz.

- Forgotten Voices of the Blitz and the Battle for Britain

- Oral history interview with Barry Fulford, recalling his childhood during the Blitz from the Veteran's History Project at Central Connecticut State University

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||